Guerrilla gardening is essentially gardening without asking — usually on publicly accessible land. Fifteen years ago the illegal practice attracted attention for its late night escapades, which resulted in neglected patches of the city made over with fragrant flowers and mini allotments. However, in recent years Transport for London’s preference for concrete paving is hindering the guerrilla gardener’s work.

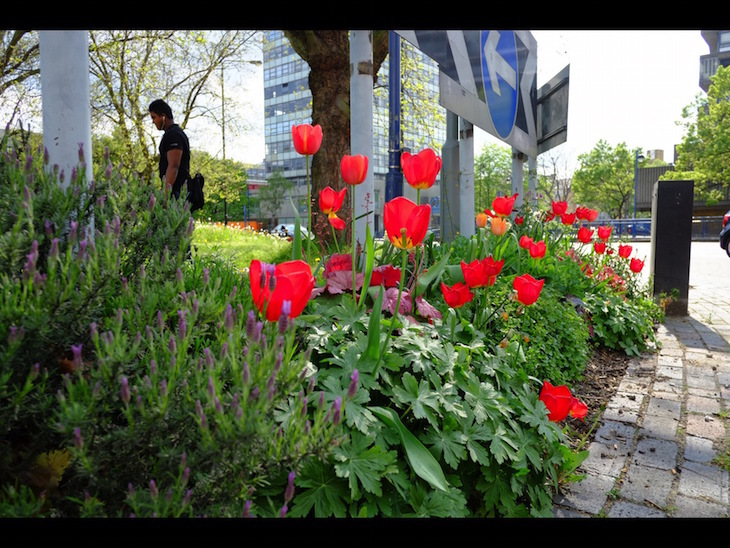

Back in 2000, Richard Reynolds — the green-fingered force behind the movement — published On Guerrilla Gardening, a handbook for gardening without boundaries. A lot has changed since then says Reynolds. “London is more intensively developed than ever, so those large scraps of marginal land — like the Elephant and Castle roundabout, like the area where we planted the lavender field — are rarer, certainly round zones one and two."

Reynolds's efforts can be seen across the city. You might have spotted the bearded gent pushing a shopping trolley full of office water dispensers through the streets of London, watering tree pits or else spreading the gospel on guerrilla gardening to horticulturalists and amateur gardeners alike.

Speaking recently at a tour organised by the Southbank Centre, he told an enthusiastic crowd about his failed attempts to persuade TfL to leave some open soil alongside all the new cycle superhighways being built.

He says despite numerous benefits from increasing drainage and biodiversity to improving mental health, TfL favours stone and concrete “not because of cost but because of aesthetics”.

“It’s this aspiration for everything to be an Italian-style piazza. Our mayor decided that he wanted to create lots of new public squares across London and the spaces he can most easily do it are on Transport for London land, so that’s what they’re shoehorning in.”

Although there is still opportunity to plant in smaller spaces, such as around tree pits or in pavements, Reynolds says “it is sad if you want to do something big or create a community garden because these days the bigger opportunities are really only temporary”.

Temporary sites can be negotiated after a bit of schmoozing with developers. The Elephant and Castle Urban Forest project within the Heygate Estate came about due to aggressive protest from Reynolds and Guy Mannes-Abbott, a writer who lives in London.

Although many trees have been felled, they successfully campaigned for some to be integrated into the developer’s plans and secured a temporary community garden, known as Grow Elephant.

But, says Reynolds, this is still a compromise. “You can get these community gardens if you can cajole the developer into letting you have a space, but they are a lot of work for just a few seasons and [the developers] can change their mind at any point.”

Reynolds grew up watching Gardeners' World but, like thousands of Londoners, was living in an apartment with no access to a garden. So he began planting up previously neglected public spaces.

“I’m passionate about seeing the potential in a space, even if it’s just about getting from A to B pleasantly and safely. It’s been tragic to see the redevelopment of Elephant and Castle roundabout — dominated by traffic, not safe for cyclists, with an actual net loss in public space.” Since its drastic redesign (to improve road safety) there have been two deaths which recently provoked an urgent safety review of the area.

Elsewhere Reynolds has documented what he calls TfL’s shameful record of unsustainable tree planting around E&C, where trees are felled for aesthetic reasons, or die because of the lack of aftercare.

According to Nick Aldworth, Head of Highways at TfL, 1,000 trees are planted every year with an average survival rate of 87%. The London Tree Officers Association (LTOA) says it's doing its best to protect trees from the increased pressures of development, as well as pests and diseases.

Becky Porter, executive officer at LTOA, says "these threats have always been present but [trees] are even more of a risk now". However she remains optimistic saying "trees have risen up the public agenda as never before and the general public now seem to appreciate urban trees more than in previous years".

The irony is that in most cases the green credentials of a development are what makes it saleable — think of the Walkie Talkie Sky Garden and the controversial Garden Bridge — “an environmental blot on the landscape,” according to Reynolds. "But when it comes to execution, those features — the water fountains, green spaces, lawns — are often the first to go because of maintenance costs."

So where does this leave the future of guerrilla gardening? Reynolds says the future lies with lots of people digging away in smaller spaces, and no longer under the cover of darkness.

The route to longevity is a passion for gardening. “In the early days it did attract a particular type of person, but I see less of them now and I’m glad of that because they’re not such good gardeners.

“It’s still very much a niche activity," he says, "but it’s becoming much more mainstream and acceptable. I’ve always been on a mission to normalise it, rather than to try to keep it exclusive and mysterious.”

London isn't averse to injecting some greenery into unusual spaces, from King's Cross Pond Club and Skip Gardens to Growing Underground, Clapham's underground farm.

In 2011 the aforementioned lavender field (below) — now 10 years old — received royal approval from the Duchess of Cornwall. And local authorities are warming up to the idea. Camden Council has published guidelines for those who are interested in looking after unused land. The council is also part of the mayor’s Capital Growth programme which allows people to grow food in unused spaces.

The charity Groundwork, which creates opportunities for people to live in a greener, more sustainable way, has helped set up community-run gardens across the city. There are now 100 pocket gardens in London which take the form of play parks, urban gyms and mini-gardens.

But is it enough? While local councils struggle to allocate funds to maintaining larger green spaces and allotment waiting lists stretch into the years, we think the more people willing to pick up a fork and get their hands dirty — to counter the sterile, concrete vision of London favoured by developers and TfL — the better. Ultimately guerrilla gardening is not just about prettifying the city, it's about reclaiming public space for everyone.

Get involved

On International Sunflower Guerrilla Gardening Day (1 May) people all over the world venture out to sow seeds in neglected public spaces — sunflowers or plants appropriate to the season.

When considering what to plant Reynolds looks for hardiness, a long impact if possible and takes into account light and shade. His advice: "be inventive, creative and resourceful and if you see a private garden and you are persuasive enough they might even let you share it".

Find your nearest pocket park using this map.