City of London guide Ian McDowell introduces us to the Square Mile's most unsettling sculptures.

The genius architects who rebuilt London after the Great Fire of 1666, Christopher Wren and Nicholas Hawksmoor, were Classicists: cool, calculating, clean. We certainly don't expect their buildings to sprout screaming heads. Cute little babies, yes. The odd rampant dragon, absolutely. A flaming phoenix — symbolising the City rising again after fire and war — most assuredly. But not this.

I was on my way to the gym one morning last autumn, eyes peeled for all things quirky, when I saw something that made my skin crawl and my eyes jump out of their sockets. I was afraid of the dark as a child, and made it worse by reading about the Enfield Poltergeist in Guy Lyon Playfair's This House is Haunted. But this was much better. This was the Hallowe'en drug of choice.

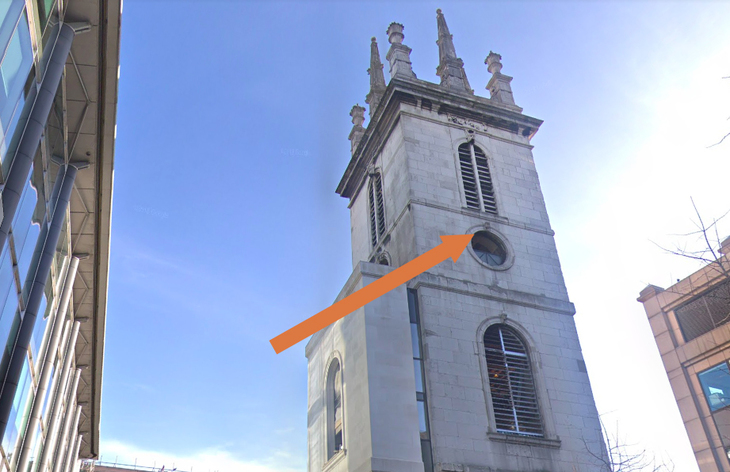

I mentioned it to one of my fellow City of London Guides, Tony Tucker, author of The Visitors' Guide to City of London Churches, and he encouraged me to do some research. He even took a photo of it, reproduced above.

It's all about bankers, of course. St Mary Somerset is extremely obscure, a tower without a church, tucked down a cutting behind St Paul's. An oligarch is converting it into a piece of residential bling, something that happens when landmarks get forgotten. It stands in a small public garden, with, to put it delicately, evidence of nocturnal activity. How is the oligarch going to get any sleep? Naughty bankers.

Bankers are the reason St Mary Somerset is a tower without a church. By the middle 1800s, the City was depopulating fast. It was the smell. The Square Mile's hundred plus churchyards had been used by unscrupulous money makers for hundreds of years to pack in as many dead bodies as possible. In some places cadavers were fifteen deep.

The Union of Benefices Act of 1860 was the Government's way of cashing in on this rapid depopulation. A sad little barn of a church, the runt of Wren's litter, St Mary's was in trouble. It was knocked down, the land sold for warehouses. But the tower was saved and "restored" by Ewan Christian, the architect most famous for creating the National Portrait Gallery.

He didn't just restore it. He added some naughty little flourishes of his own to unsettle the visitors of the future. Strictly, the screaming head is a carved keystone, not a gargoyle. There is no gargoyle-like playfulness about it. It is deadly serious. It reminds me of nothing more than Edvard Munch's The Scream (1893). As far as we know, Munch didn't visit London until 1913, but might he not have taken the boat train from Paris in the 1890s for a look around? The resemblance is certainly astonishing.

More likely, the influence is the other way round. Christian would certainly have seen John Leech's 1843 imagining of Marley's ghost from Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol who famously undoes the napkin supporting his deceased jaw to devastating effect. Look up at this screaming head, and you will feel as Scrooge must have felt when he realised his friend and business partner was not going quietly to his grave.

The loss of an historic church to Government bulldozers. Warehouses planted on suppurating graveyards. All this must have put Ewan Christian in mind of death. And Scrooges. Edvard Munch took up the same theme, thirty years later. The rest, as they say, is a certain kind of history.

Images that outstare the grave. Pass them on, as Hector says in The History Boys. Pass them on.

The screaming keystone head of St Mary Somerset can be sampled on Lambeth Hill, the City of London.

Ian McDowell runs Dark Side Walks, including the Hilarious Heritage Walk (a celebration of British eccentricity) Saturdays at 2pm. "Ian McDowell's Dark Side Walks are as funny as they're dark. As nineteenth century poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge said, 'Comedy is the flower on the nettle'."